We’re Tar Heels.

We work hard.

We play hard.

We play smart.

And we always play together.

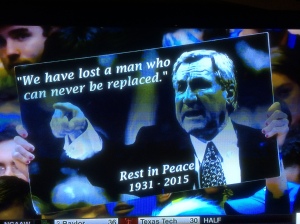

That was Coach Smith’s credo as remembered by Erskine Bowles during the public celebration of Coach Smith’s life held under the dome of the UNC Student Athletic Center. Bowles, a former UNC system president, is the son of Skipper Bowles and Smith family friend. Skipper chaired the charge for building the basketball arena working alongside with Smith.

It was a very moving day of storytelling, personal and fond memories shared, all to make sure that people now knew as much about their great coach, friend, mentor and father, as possible.

Many have remembered our legendary jewel of a coach, both before and after he passed away this month. He’s a coach who drew attention from the moment he stepped into the hot spotlight that was Carolina basketball. He took over a team that was in trouble not long after winning a national championship. Frank McGuire, his head coach, had left for the NBA. With his hands tied by self imposed restrictions by the university, Smith, as head coach, began to build what became the “Family of Carolina Basketball.”

Many have remembered our legendary jewel of a coach, both before and after he passed away this month. He’s a coach who drew attention from the moment he stepped into the hot spotlight that was Carolina basketball. He took over a team that was in trouble not long after winning a national championship. Frank McGuire, his head coach, had left for the NBA. With his hands tied by self imposed restrictions by the university, Smith, as head coach, began to build what became the “Family of Carolina Basketball.”

Fittingly, one of the first to speak was Mickey Bell, a former walk-on player. Bell said that Coach Smith “was the most positive man I ever met. In game defining moments, Coach said things like ‘When we make the free throw, not “if.”‘ He never talked about winning. He only talked about improving.

“Preparation leads to calmness,” continued Bell. “When the Heels were down eight points with 17 seconds to go against Duke, Coach Smith called a timeout. In the team huddle he said, ‘We’re in great shape. Isn’t this fun.'”

I want to share an important part of the Dean Smith story from an article written by John Feinstein and published last year on February 28th to honor Smith’s 83rd birthday. Knowing Dean’s declining health and diminished memory, John recalled and retold a 1981 interview with Smith in which he learned even more about the coach’s character and principals in the game of life. John, an alumnus of Duke, tells it like this:

There’s one story that — to me — defines him. I’ve told it in the past, but it bears re-telling. In 1981, Smith very grudgingly agreed to cooperate with me on a profile for this newspaper. He kept insisting I should write about his players, but I said I had written about them. I wanted to write about him. He finally agreed.

One of the people I interviewed for the story was Rev. Robert Seymour, who had been Smith’s pastor at the Binkley Baptist Church since 1958, when he first arrived in Chapel Hill. Seymour told me a story about how upset Smith was to learn that Chapel Hill’s restaurants were still segregated. He and Seymour came up with an idea: Smith would walk into a restaurant with a black member of the church.

“You have to remember,” Reverend Seymour said. “Back then, he wasn’t Dean Smith. He was an assistant coach. Nothing more.”

Smith agreed and went to a restaurant where management knew him. He and his companion sat down and were served. That was the beginning of desegregation in Chapel Hill.

When I circled back to Smith and asked him to tell me more about that night, he shot me an angry look. “Who told you about that?” he asked.

“Reverend Seymour,” I said.

“I wish he hadn’t done that.”

“Why? You should be proud of doing something like that.”

He leaned forward in his chair and in a very quiet voice said something I’ve never forgotten: “You should never be proud of doing what’s right. You should just do what’s right.”

In their first home game after Coach Smith’s passing , Carolina took on Georgia Tech. Julie and I were standing six feet from the TV expecting something special to happen. It did.

Coach Roy Williams honored his coach and mentor in the best way he knew how. On the first Carolina possession, he raised his hand calling the play. Four fingers signaling Smith’s famous “Four Corners” offense. Play by play announcer Wes Durham, son of legendary Tar Heel sports broadcaster, Woody Durham, caught on quickly as the camera cut to a shot of Roy with his four fingers held up high. I looked over at Julie, smiling through tears and said, “He’s calling for Four Corners!” I choked up as I said in all honesty, “I hated the Four Corners! I hated it. But I love this moment.”

Then Marcus Paige, playing Phil Ford’s position in the center, spotted Brice Johnson cutting to the hoop, threaded a pass to him for a reverse layout. It was one shining moment on the court and a fitting tribute for the coach and to the crowd.

And I did hate the Four Corners. See, I grew up in a family of die-hard NC State Wolfpack fans who shared their love of the Pack with their kids. We shared the common thrill of gathering around the black and white TV to watch the one camera, silent telecast of NC State games on UNC public television. We’d listen to play by play on the NC State radio broadcast. Yes, we loved the Big Red. So, naturally, we hated Duke and Carolina. Especially Carolina. It seemed like the whole state worshipped Carolina Blue except for the Rileys. And anyone except for UNC fans hated the Four Corners. It controlled the tempo, protected leads, and slowed the game to a snail’s pace. The shot clock took care of that. And yet, Coach Smith’s teams continued to win, year in and year out because he continued to innovate with his players and the game.

Even while attending UNC from 1971-75, it took me some time to warm up to my own school team. Hard to fathom probably for many of my friends today since I’ve swung full tilt to Carolina Blue over the years. But I still love NC State. It meant family to me growing up, joined in a passion and love for something special. It still means that today. I turned around and gave my kids the same unifying experience of yelling at the TV as my Tar Heels played and we cheered hard together for every victory and loss we could watch while living in Pittsburgh and Atlanta. Cheering for the Heels meant home. Home in North Carolina.

I want to share my own Dean story about when and how I actually met him. I didn’t meet him until I suffered through an embarrassing moment in my career as a fan.

I was working for WPXI-TV in Pittsburgh. Dean’s tradition of putting an early road game on the schedule against a school in or nearby his seniors’ home towns brought the National Champions to Pittsburgh in December of ’93. Kevin Salvadori, was the senior player and native Pittsburgher I had to thank for the Heels’ visit. We had been living in Pittsburgh for eight years. I can only say that a combination of homesickness and an overabundance of championship pride drove me to the depths of “fandamonium.” I secured tickets for the four of us way in advance. As the day drew near, I developed an almost desperate need to score team autographs from this opportunity. After all, they were the reigning National Champions.

Julie bought one of those little commemorative Tar Heels basketballs for me and I took it to the game. We got over to the Civic Arena early enough to see the shootaround. I took my ball and Sharpie courtside and went to the end where the team was warming up. It was me and about 10 kids under 12 years old, hanging around the basket shuffling for attention with our sharpies in our hands. A security guard came over, looked at me with sad acknowledgement before shooing us away. I moved around the corner to behind the team bench and recognized Phil Ford on the floor talking to some folks who obviously belonged on the floor. I yelled, in a whispered voice, “Phil! Phil!” I didn’t catch Phil’s attention, but I did raise the guard’s attention again. He moved over my way and with a look of “Are you serious?” and dismissed me with a wave that strongly suggested that he’d better not see me again.

We enjoyed watching our team play and defeat Pittsburgh that night, but being so close to the team and not getting many autographs drove me crazy. After the game, as we were leaving the arena, I saw the team bus in the loading dock area. I ushered Julie and the kids to the car in the upper parking lot and went back down near to the bus. There were a few other people standing there where a chain link type gate kept us out of the huge passageway. As I waited, I recognized Eric Montross’s father standing in the small crowd. I had seen him numerous times on TV, watching Eric play. He, like his son, was quite tall. I spoke to him for a minute and he said that the kids would be coming out shortly. Finally, the gate rose and out walked the team. I did get a few autographs which have faded to be almost unreadable. I remember Pat Sullivan took the time to write his name on the ball as did Montross. When I finally got back to the car I met a very unhappy family. How could I leave them to be the last car in the lot? And, it was December and cold. How could I? Only one explanation. I’d become pretty darned invested in my Carolina Tar Heels while living away from home for so long.

Next time up came two years later. Dante Calabria, a sharp-shooting kid from Beaver Falls, PA was the senior. This time, I worked the inside route, asking Sam Nover, our sports director, for advice. He told me to show up at the press entrance. He knew the team was practicing in the early afternoon. He’d leave word at the security gate to let me in.

Although it was not without a moment of pause when the security guard wasn’t so accommodating. This was pre-cell phone days so I couldn’t raise Sam’s attention. He was inside. I was facing an unbelieving guard who didn’t seem to want to go out of his way to verify my story. Thankfully, a more customer service oriented employee stopped by, and took me in. I walked through a long dark hallway that came out right on the Igloo’s floor. It’s an amazing way to enter a building like that. The rows of chairs were laid out filling up the end zone area. I walked down the aisle leading to court from behind the backboard. I came up on a few folks talking in the aisle. One man turned my way, saw me, smiled and said, “Why hello. I’m Bill Guthridge.” I had recognized him in the instant I saw his face and before he spoke. And now it was my turn to explain myself. “Nice to meet you, Coach Guthridge. I’m Steve Riley, class of ’75. I work here in Pittsburgh for WPXI-TV, the NBC affiliate.” Guthridge gave me a very warm handshake. “Well how about that. That’s great. Hey Coach!” he said turning and walking me right up to Coach Smith who was standing nearer to the court where the team was scrimmaging. “This is Steve Riley, class of 75. He works for WPXI-TV here in Pittsburgh!”

“Why hello Steve. It’s great to meet you. Thanks for coming down.” That’s what I remember Coach Smith saying as he gave me a warm handshake. “Hey fellas,” he shouted to guys as they were walking off the court. “Come over here and say hi to Steve Riley, class of ’75. He lives up here in Pittsburgh working for the local TV station, WPXI-TV.” And that’s how I met Coach. And Antawn Jamison, Vince Carter and, of course, Dante Calabria. I had a Sports Illustrated with me that had the Tar Heels on the cover and a Sharpie. Those guys gave me their autographs. Dean gave me something that meant so much more, his hand and recognition.

All through his life Coach Sm ith did what was right. He honored the game, our school, our team and the boys who became men all at the same time.

ith did what was right. He honored the game, our school, our team and the boys who became men all at the same time.

He did win ball games. But he also won hearts.

Rest in peace, DES.